- Home

- Rebecca Levene

The Hunter's Kind: Book II of The Hollow Gods Page 8

The Hunter's Kind: Book II of The Hollow Gods Read online

Page 8

‘They’re behind too, brother.’

Krish glanced at Olufemi, but her expression didn’t offer much hope. She looked panicked.

‘The runes, mage!’ Dae Hyo hissed. ‘Use the runes!’

She blinked as if the thought hadn’t even occurred to her, and then flung her bag to the ground and began desperately rooting through it. ‘I think there’s a chalk, yes, I think …’ She’d grasped it in her hand when the crocodiles charged.

Krish flung himself in front of her, a protective instinct he didn’t fully intend. Dae Hyo tried to fling himself in front of Krish in turn, and they ended up shoulder to shoulder in front of the mage, a sword in Dae Hyo’s hand and Krish still fumbling his knife from his belt. Dae Hyo’s blade slashed at one of the beasts as it hurtled towards them, every bit as fast as Olufemi had warned. The blade bounced uselessly from the thick scales and then the creature was past and all the others with it, and not a single one had even snapped its long jaws at them.

Krish turned, shaking, to see that the crocodiles had found other prey. They were clustered in a horrible feeding frenzy over a victim who remained hidden by their massive bodies, only scraps of clothing and flesh visible as the predators tore them free. Better him than us, Krish thought, except he was sure it would be them next.

But then something else landed among the vicious jaws and for just a moment he saw it clearly: a hunk of meat wrapped in cloth. The crocodiles fell on it too and Krish looked beyond them to see the man who’d thrown them their food.

The man raised a lazy hand to wave when he saw them looking. ‘Olufemi,’ he said in lightly accented Ashane. ‘A long time since you’ve visited us and a dangerous way to return. Could you not wait for a guide? We’d have sent a boy to bring you through safe if we’d known.’ He threw the beasts another bloody chunk.

‘I couldn’t wait, Uin. I’ve news for you and enemies who’d stop me bringing it.’

Uin threw the last of his meat away and came towards them through the crocodiles, hopping over their tails with no sign of concern. He was shorter than Dae Hyo and perhaps a little darker, but his features were definitely those of a tribesman. Still, there was something about his face, the way he held himself, that seemed quite foreign. His eyes were cautious and narrowed as they flicked over Dae Hyo and Krish.

‘You bring strangers to our lands, Olufemi, where no strangers are welcome.’

‘I bring you your god,’ Olufemi said. ‘Will you let him pass?’

Uin’s eyes settled on Krish, now wide and full of wonder.

Uin had given them mounts to ride, some relative of the crocodiles five times their size. Their backs were so broad Dae Hyo sat cross-legged on the saddle, and he wobbled uneasily as the monster waddled forward. Its splay-legged stride ate up the distance with ease and the crocodiles were soon lost to sight behind them, probably still squabbling over the last of their meal. He saw others lift their heads from streams and ponds as they went past, but when they realised no food was being offered, they quickly sank down again.

Gradually, the landscape changed, the water remaining but the drooping plants and dense trees diminishing until there was little but low grass on the riverbanks.

Soon the grass itself had been replaced by a patchwork of neat green squares. People laboured in these half-drowned fields, though Dae Hyo couldn’t guess what crop they were tending. There’d be no game here, no deer roaming in this endless farmland.

The path their mounts followed broadened until their great clawed feet began to make a hollow sound with every step and Dae Hyo realised they were walking on wood. It was a road and all around was not wilderness but civilised land. He saw floating platforms with crops of brightly coloured flowers rooted on them. There was a field of red blooms, another of purple and then one of soft green ferns. Nothing here seemed to grow out of place or out of line. The orderliness of the Rah territory now being revealed was all the more startling for the veil of savagery behind which it hid.

Finally they came to the settlement and their mounts dawdled to a stop. Of course there were no tents here: the Rah thought themselves too good to live as the other tribes did. Instead they’d built houses, dark-stained wood like those of burnt Smiler’s Fair, but to an entirely different design. Their homes were low and sprawling and widely separated. No, Dae Hyo realised, entirely separated. Each was constructed on its own floating raft of reeds. He saw two men hook up a crocodile to the far edges of one raft and drag it away through the water. Their houses were as mobile as any Ashane landborn caravan and far bigger. It was clever, in a Rah sort of way.

While he stared, Uin dismounted and crossed to Krish, bowing and reaching up a hand. ‘Will you come with me, great lord? Your people wait to meet you.’

It was true. Groups of men and women were emerging from all the scattered houses, soberly dressed in the Rah style but with a bright excitement in their faces. Word had clearly travelled ahead and they poled their flat-bottomed boats towards Krish: close but not too close, as if they were afraid to touch him, or maybe afraid to offend him.

His brother looked baffled. Olufemi had said he was a god, but she hadn’t said what kind. Dae Hyo loved Krish as well as any man loved his brother, but he didn’t think anyone would mistake him for one of the more warriorlike of the pantheon. He seemed like a scribe for one of the greater gods, clever and necessary but hardly a figure of awe. Especially not smeared in mud as he was right now.

Except the Rah men and women clustered about did look awed. They smiled at Olufemi, barely even noticed Dae Hyo and kept their – well, he had to be honest – their worshipful gazes on Krish. It was almost insulting.

Uin didn’t seem keen to share his prize with his brethren. He put a proprietorial arm round Krish’s shoulders, which made both Krish and Dae Hyo stiffen, and ushered him inside the nearest house.

In their disappointment, the rest of the Rah finally turned to Dae Hyo and he smiled at them as he followed his brother and Olufemi indoors. The Rah were barely members of the Fourteen Tribes; they’d turned themselves into sit-still people just like the Ashane. But the Rah weren’t currently trying to kill him, and that was good enough to be getting on with.

Inside, Uin let them wash at last and gave them fresh clothes – Rah clothes. Dae Hyo squirmed uncomfortably and followed his host to the dinner table. The mage had kept her own robes, muddy as they were, but Krish too was in borrowed brown. Dae Hyo didn’t like the way his brother looked in the sombre hemp shirt and trousers. He didn’t look Dae.

The food wasn’t Dae either. There was a lot of it, but he suspected the meat was snake. It was pale yellow and dripping with grease and not at all something he wanted to put in his mouth. He did it anyway, determined to be courteous.

Uin talked expansively, telling Olufemi of the messages he’d sent out announcing Krish’s arrival and the important men who’d be flocking to meet him. Olufemi nodded as if she believed him, but so far all he’d brought to the table were his wife and two daughters, the three of them so meek and quiet they barely added up to one person’s worth of conversation between them. The girls were no older than Krish and the mother a beauty pared by time to unappealing boniness.

When Dae Hyo speared the last greasy chunk of meat from his plate, a woman drifted forward to serve him more. He saw Krish eyeing her askance and it was clear why: she was Ashane – a slave, although his brother probably didn’t realise that. The Moon Forest boy who’d brought their clothes was a slave too, and the tribeswoman they’d glimpsed bent over the pots in the long, low kitchen. And all of them had the dreamy expressions and dead eyes of those that drug, bliss, had its hooks in. Krish didn’t know what rat-fuckers these Rah really were.

And Uin was doing everything he could to stop Krish realising it. The man knew how to be charming and he had stuck to speaking Ashane the moment he realised his god had a shaky grasp of the tribe’s own tongue. He smiled as he leaned across and refilled Krish’s glass with the thick, sweet wine these Rah seemed to like.

Krish had already drunk two glasses and Dae Hyo knew he wasn’t used to it. His cheeks were flushed and his eyes glazed. Not a state for good judgement, as Dae Hyo knew well enough. At the moment, Krish was staring rudely over his host’s shoulder.

‘Ah,’ Uin said, following the direction of Krish’s gaze. ‘You’re admiring our serpents. There’s no need to fear, great lord. Even if they could get loose from their tanks, we’ve milked all the venom from them.’

‘You milk snakes?’ Dae Hyo asked. ‘I can’t imagine it’s good drinking.’

Uin’s smile thinned as his attention switched from Krish to Dae Hyo. ‘Do you know the best antidote for venom, warrior?’

‘Not being bitten.’

‘The venom itself. Like any painful thing, our bodies grow calloused against it until it can no longer hurt us. When you people invaded us—’

‘It was the Four Together, not the Dae!’

‘When our cousin tribes decided to take our grazing lands, we let the wilderness claim our new border. And then we drank the venom of all the snakes that came to make their beds there, a little more every day from our youngest age, until the bite that would be death to any invaders was nothing to us. Now no one comes here uninvited.’

‘You’re saying we’re safe here?’ Krish asked.

‘Great lord, we would spend our lives to protect you.’

‘But you’d prefer the snakes to spend theirs.’

That surprised a laugh from Dae Hyo but Uin seemed affronted. His cheeks sucked in until his face looked as long and unfriendly as a snake.

‘Krishanjit means no offence,’ Olufemi said hastily.

‘What? No!’ Krish thumped a hand on the table with a little too much force, so that the clay plates jostled and clattered. ‘I think it’s … it’s clever. Why fight when you don’t have to?’

‘But I’ve told your people,’ Olufemi said carefully, ‘that you’ll lead them to victory against their enemies. That your ascendancy will mark the time of theirs too.’

‘The Rah aren’t his people!’ Dae Hyo snapped. ‘We’ve only come here to get away from those rat-fucking Ashane scum. My brother is Dae.’

‘Krishanjit is of all peoples, and of none,’ Olufemi said.

‘But Lord Krishanjit has come to lead us,’ Uin said. ‘Isn’t that true, great lord?’

Even the slaves turned their dazed eyes to watch as Krish looked between their host, Dae Hyo and Olufemi. Uin’s wife seemed to be holding her breath and the oldest daughter twisted her hands in her lap. Dae Hyo realised he’d clenched his own fist and made himself loosen a finger at a time and rest them on the table. He didn’t need to doubt his brother.

‘Yes,’ Krish said, ‘I have come to lead the Rah.’

Uin nodded as if it was the answer he’d expected all along, and Krish never saw Dae Hyo’s shock, because his eyes stubbornly refused to turn to his brother.

7

Marvan woke coughing, as he had every morning since the fire that took Nethmi from him. He pulled himself upright and let the cough continue until he could spit out the gobbet of phlegm and soot that had been lodged in his lungs. The fire had taken his health from him too, but he found that he didn’t much care. He’d known Nethmi only a few days and it seemed improbable and foolish that her absence could feel so vast to him, but there it was. There were so few people in the world who were unlike all the rest, and he’d lost the only other one he’d ever met.

Hunger gnawed at his stomach. He contemplated not eating, but starving to death wasn’t the way he’d choose to go, and besides he was sure he’d feel less wretched soon. He’d never realised how useless love was. What was the point of a feeling so tenacious it could survive even the death of its object?

He’d salvaged nothing from the fire; his only possessions were the clothes on his back and his twin tridents. His cat Stalker had either burned or fled and he’d slept alone on the ground and left a damp hollow when he rose.

Work was an option, but not an attractive one. Robbery seemed preferable. He’d resorted to it only once before, when he’d purloined the mammoth from his family’s stables that he had used to buy membership in the company of Drovers. Back then the risk had been slight. His family would rather have lost the mammoth than retrieve it and admit one of their scions was a thief.

This time he couldn’t afford to get caught. Many more Jorlith than others had survived the fire, their enforced sobriety and gateway stations having placed them in the best positions to flee. Now they earned their bread by keeping order among refugees who might otherwise descend into a rabble. Marvan had seen a boy hanged yesterday, and he’d only stolen a chicken. Any witnesses to Marvan’s own crime must be eliminated.

He’d slept a little distance from the remnants of the fair and the walk back over a small hillock gave him a good view of it. It was a pitiful thing, barely a hundredth of its original size. The streets were laid out in an echo of their old arrangement, but there were buildings missing in each of them, like rotten teeth fallen from a diseased mouth, and those that remained were blackened with soot.

Animal pens sprawled to the left of the fair and nearby the survivors of the Merry Cooks had set up shop, a haze of smoke hanging over their stalls. His mouth watered and he spat again to clear it before sitting down. He didn’t intend to snatch just a few crusts or one roasted bird, like the careless hanged boy. It was money he wanted, and the cooks were among the few residents of the fair who still had a way to earn it. They had bladders and guts too, and they’d need to empty them.

He watched the clouds drifting until he saw the first figure detach itself from the crowd. His stomach clenched in anticipation until he realised it was a woman. He’d killed a girl once but it had given him no satisfaction. It was like eating potatoes when you hungered for meat.

Another woman followed and then two men together, perhaps heading out for more than a piss. Then, finally, a man alone wandered from the safety of the rest. His path would take him behind the hillock Marvan occupied and no scream would carry from the lee of the mound to the other Merry Cooks.

Marvan waited until the other man was out of sight of the fair before descending to meet him. The cook looked up, his cock limp in his hand, as Marvan’s shadow fell over him. ‘Marvan!’ he said. ‘And here was me thinking you’d died in the flames along with all the rest. I shall have to tell Fat Pushpinder – she was asking after you only yesterday. So did you hear the chatter?’

It was Damith the baker. Damith, who’d first told Marvan of Nethmi’s crime and led him down the path that ended here. Marvan shifted the tridents in his hands, flipping them to sit along his forearms so they’d stay hidden as he approached.

‘You know I don’t listen to gossip, Damith.’

‘Oh, you say that, but every man likes to know what every other man is doing and better yet when it’s something disreputable. Isn’t that right, Marvan?’ Damith’s voice remained calm as he spoke but he’d left his cock hanging loose, his hands trembling beside it.

He knew, Marvan realised. Damith didn’t need to see the tridents to guess what was coming but Marvan showed them to him anyway. Just because this killing was from need didn’t mean he couldn’t enjoy it. ‘I don’t really care what anyone else does or thinks,’ Marvan said.

A sudden spurt of piss came from the end of Damith’s cock as fear made his bladder realise it had a little more to give. ‘This is tasty fare, Marvan, I promise. I promise. Seonu Sang Ki has found his father’s killer, and what do you say to that?’

Marvan was almost within striking distance. ‘I wish him joy of his justice, whoever he is.’

‘But there’ll be no justice, not yet.’ Damith was gabbling now. It was fitting, Marvan supposed, that he wanted to spend the last moments of his life as he’d spent so much of the rest of it: passing on meaningless gossip. ‘The woman’s pregnant with Lord Thilak’s own child, or so they say, though I say they won’t be certain till the baby pops out brown and noble-looking.’ His sm

ile was ghastly. ‘This Nethmi was in Smiler’s Fair long enough to find a thousand other fathers if she liked, and who doesn’t like that sort of thing?’

The tridents landed on the grass with a thud softer than the sudden pounding of Marvan’s heart. ‘Nethmi? Nethmi is alive?’

Damith smiled tremulously. ‘There, you see. I knew you only pretended not to care.’

It wasn’t easy to enter the Ashane camp. Armed guards ringed it and they had the uneasy looks of men who felt themselves in enemy territory.

‘I need to speak to Seonu Sang Ki,’ Marvan told the nearest.

The man was skinnier than a landborn farmer’s horse. ‘Only Ashane get in to see the boss,’ he said.

‘I am Ashane,’ Marvan pointed out.

‘Proper, I meant, not Smiler’s Fair scum.’

‘I am Marvan of Fell’s End, Lord Parmvir’s son.’

The man frowned suspiciously at him. ‘Then why aren’t you in Fell’s End?’

It was a reasonable enough question and not one whose answer Marvan felt like sharing. He’d meant to save his choicest morsels of information until he was in front of Seonu Sang Ki himself, but it was clear that wouldn’t do. ‘I come bearing news of your fugitive,’ he told the guard.

‘What fugitive?’

Marvan sighed and then regretted it as the soldier’s knuckles whitened on his sword hilt. ‘I mean this Krishanjit,’ he said. ‘King Nayan’s long-lost son.’

‘You know where he is?’

‘I know where he was. Do you think that might be of interest to your lord?’

They brought him to the centre of the camp. Seonu Sang Ki was easy enough to spot, although Marvan had never met him, but if his mixed blood hadn’t singled him out, his vast bulk most definitely would. Marvan had never seen a man so fat and he couldn’t help marvelling at that grotesque stomach before his eyes rose to meet Sang Ki’s. They were full of a shrewd intelligence that knew quite well what Marvan had been staring at. He realised he’d need to be careful.

Smiler's Fair: Book I of The Hollow Gods

Smiler's Fair: Book I of The Hollow Gods Cold Warriors

Cold Warriors The Quartz Massacre

The Quartz Massacre The Hunter's Kind: Book II of The Hollow Gods

The Hunter's Kind: Book II of The Hollow Gods Kill or Cure

Kill or Cure Bad Timing

Bad Timing Grand Thieves & Tomb Raiders

Grand Thieves & Tomb Raiders Ghost Dance

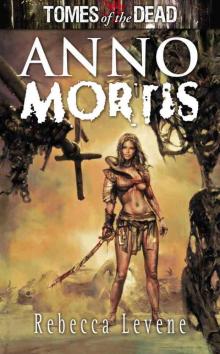

Ghost Dance Anno Mortis

Anno Mortis